It’s hard to imagine anything alive that was born in 1505. That was the year Martin Luther became a monk and King Henry VIII called off his engagement to Catherine of Aragon… in short, a long time ago. But that’s exactly what scientists believe they have found in the form of a huge Greenland shark swimming in the icy waters of the Arctic Ocean. The shark is estimated to be up to 512 years old, which would make it the oldest living vertebrate in the world and even older than Shakespeare. . And you thought turning 30 made you old.

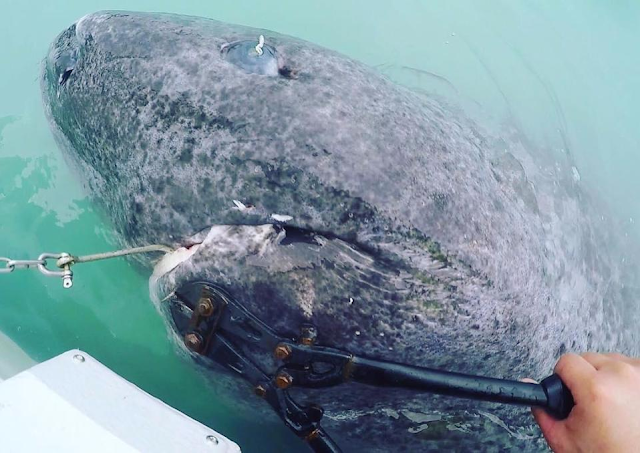

Greenland sharks are known to live for hundreds of years and spend most of their lives swimming in search of a mate. It’s a long waiting time. They also grow at a rate of one centimeter a year, allowing scientists to determine their age by measuring their size. This particular shark, one of 28 Greenland sharks that scientists will analyze, was 18 feet long and weighed more than a ton, meaning it could be between 272 and 512 years old.

The shark’s potential age was revealed in a study in Science magazine, according to The Sun. If scientists had gotten the shark’s age right, it would have been alive during major historical events like the founding of the U.S., the Industrial Revolution, and World War II. Wars. Crikey. Greenland sharks primarily eat fish, but have never actually been observed hunting. Some have even been found to have remains of reindeer and even horses in their stomachs. The animal is a delicacy in Norway, but its meat is poisonous if not treated properly.

Because of their longevity, academics in Norway believe the bones and tissues of Greenland sharks can give us insight into the impact of climate change and pollution over a long period of history. Researchers at Norway’s Arctic University are currently mapping the animal’s DNA, looking at its genes to learn more about what determines lifespan in different species, including humans. Since many of the sharks predate the Industrial Revolution and large-scale commercial fishing, sharks have even been called “living time capsules” that could help shed light on how human behavior affects the oceans. “The longest-lived vertebrate species on the planet has formed several populations in the Atlantic Ocean,” Professor Kim Praebel said at a symposium organized by the Fisheries Society of the British Isles. “It is important to know so we can develop appropriate conservation actions for this important species.”